Following their precipitous meeting at the famed Bauhaus school in 1922, artists Josef and Anni Albers, arguably the most enduring couple to emerge from the Bauhaus movement, would chart the rest of their lives as a kind of two-person artistic powerhouse. Despite spending more than half a century together and enjoying flourishing individual careers, though, there were only three occasions on which the Albers’ collaborated artistically: Easter, New Year’s, and Christmas.

The Albers had “the utmost respect for one another’s work,” says Nicholas Fox Weber, executive director of the non-profit Josef & Anni Albers Foundation, who was a close personal friend of the couple’s, and wrote the 2020 visual biography Anni & Josef Albers: Equal and Unequal. But the couple, who married in 1925, were content to remain solidly in their own spheres. “She was the weaver and he was the painter, and neither was going to get into the other’s realm,” Weber explains.

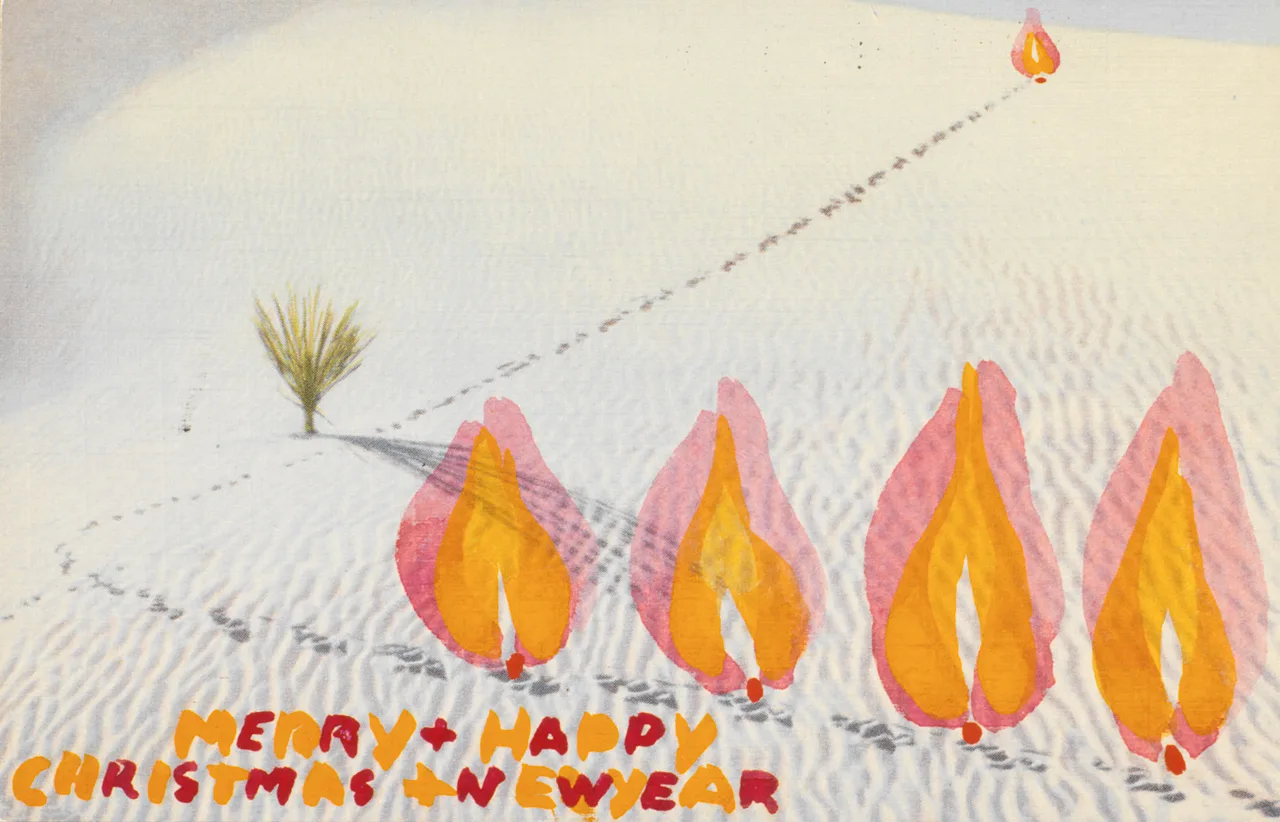

They would, however, stray from that rule for those three select holidays, during which they worked together to make commemorative art. True to their innovative perspectives, the Albers’ holiday cards aren’t merely simple greetings, but rather uniquely design-centric takes on the holiday tradition. They also provide a rare glimpse into how two of the most influential recent designers enjoyed Christmas as a couple.

A BAUHAUS APPROACH TO GREETING CARDS

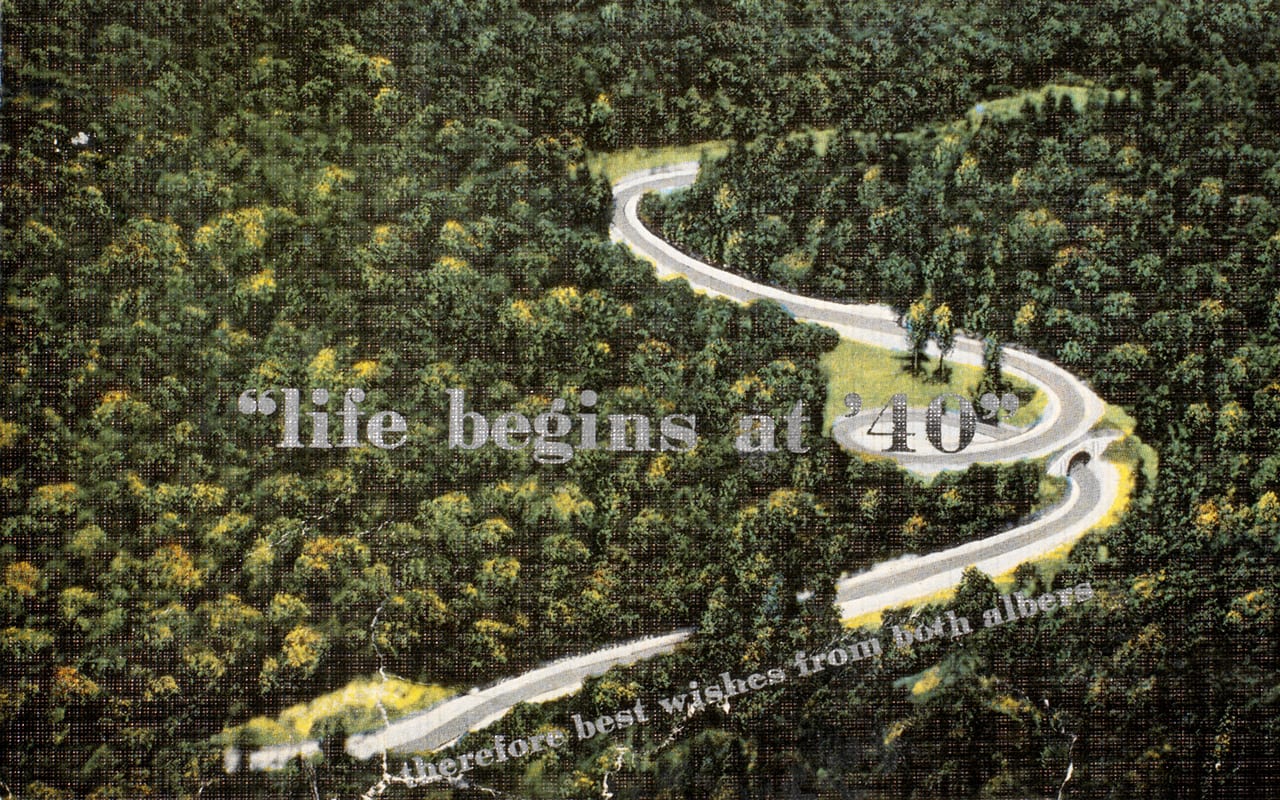

The Foundation’s collection of the Albers’ holiday cards begins in 1934, at the start of a new chapter in the couples’ lives. The year prior, the Bauhaus was forced to close by political pressure from the Nazi party—pressure that also spurred the Albers to relocate to the U.S. Both Josef and Anni took up teaching positions in North Carolina at Black Mountain College, a location that inspired several of the Christmas cards to come.

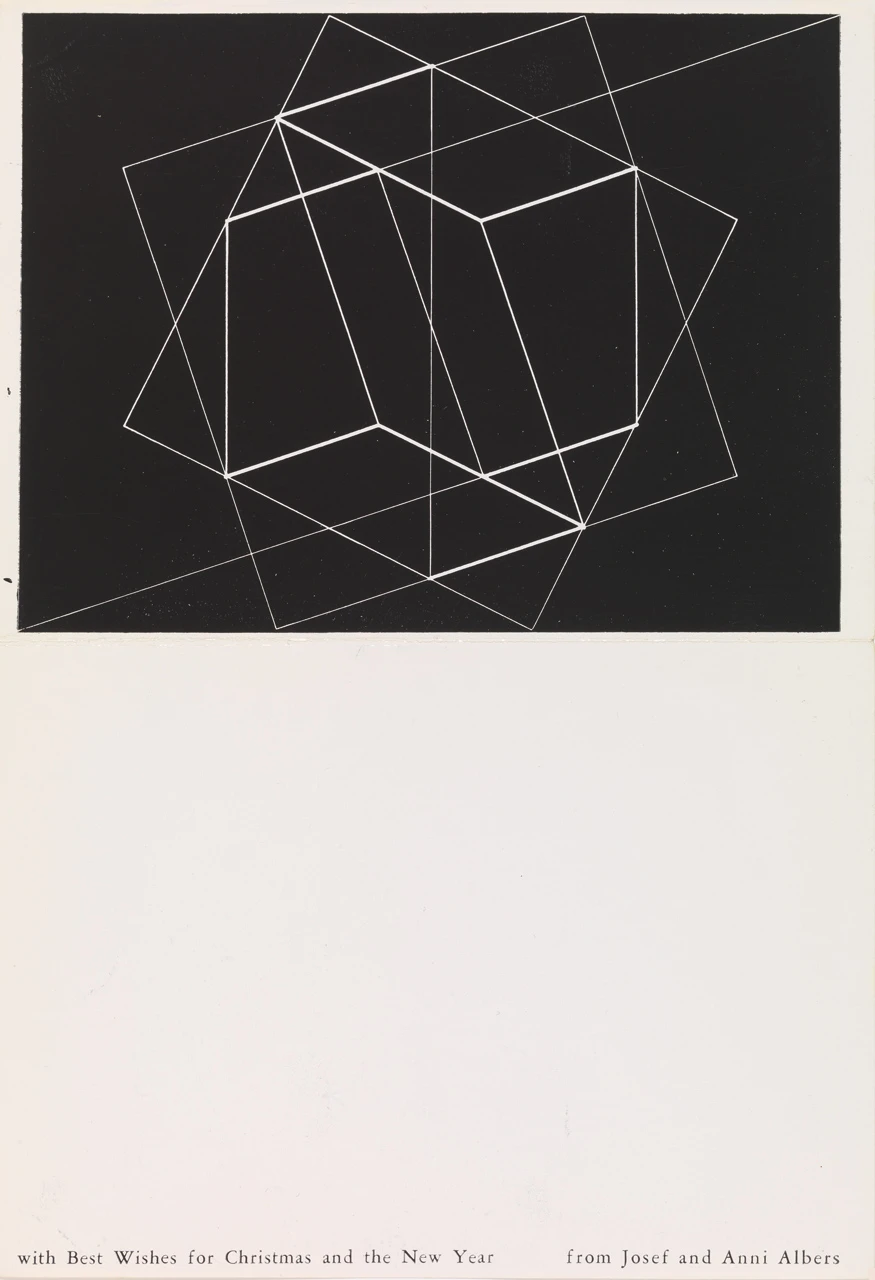

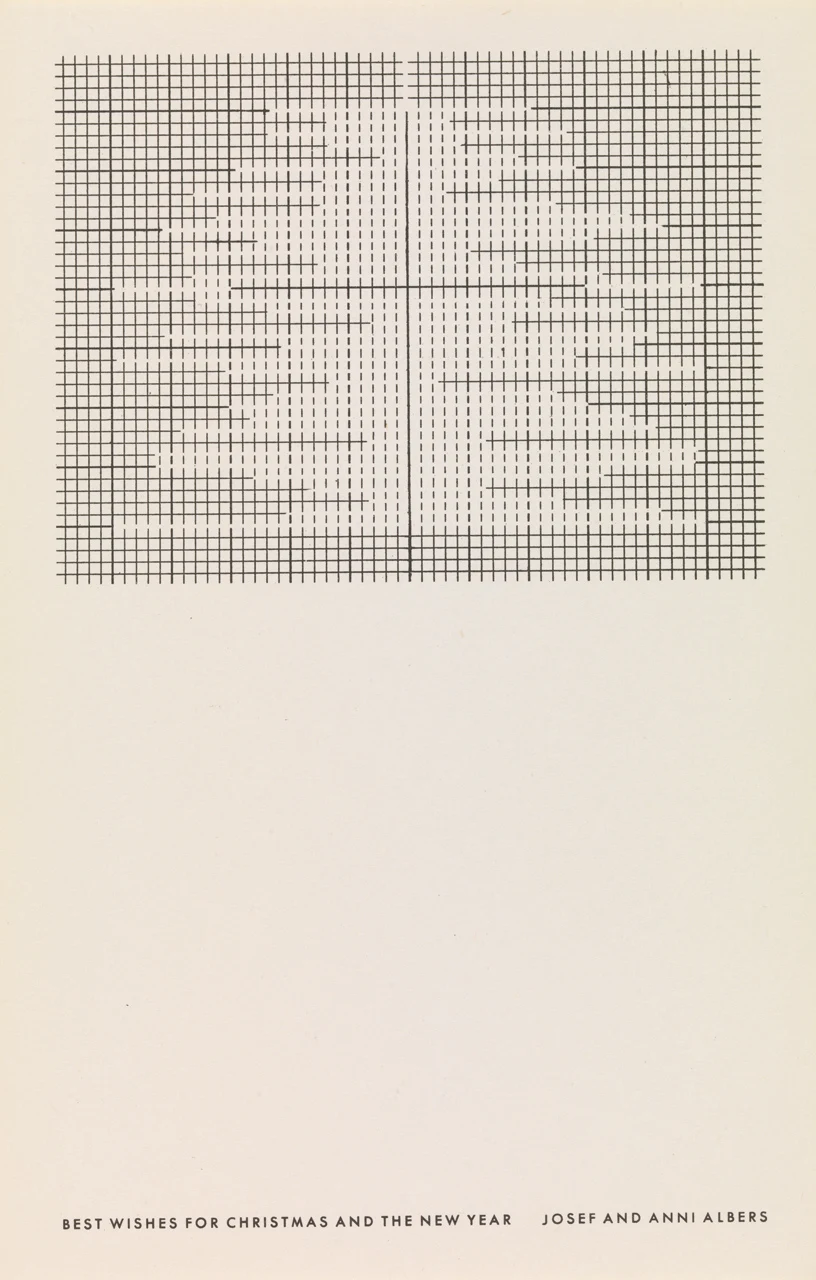

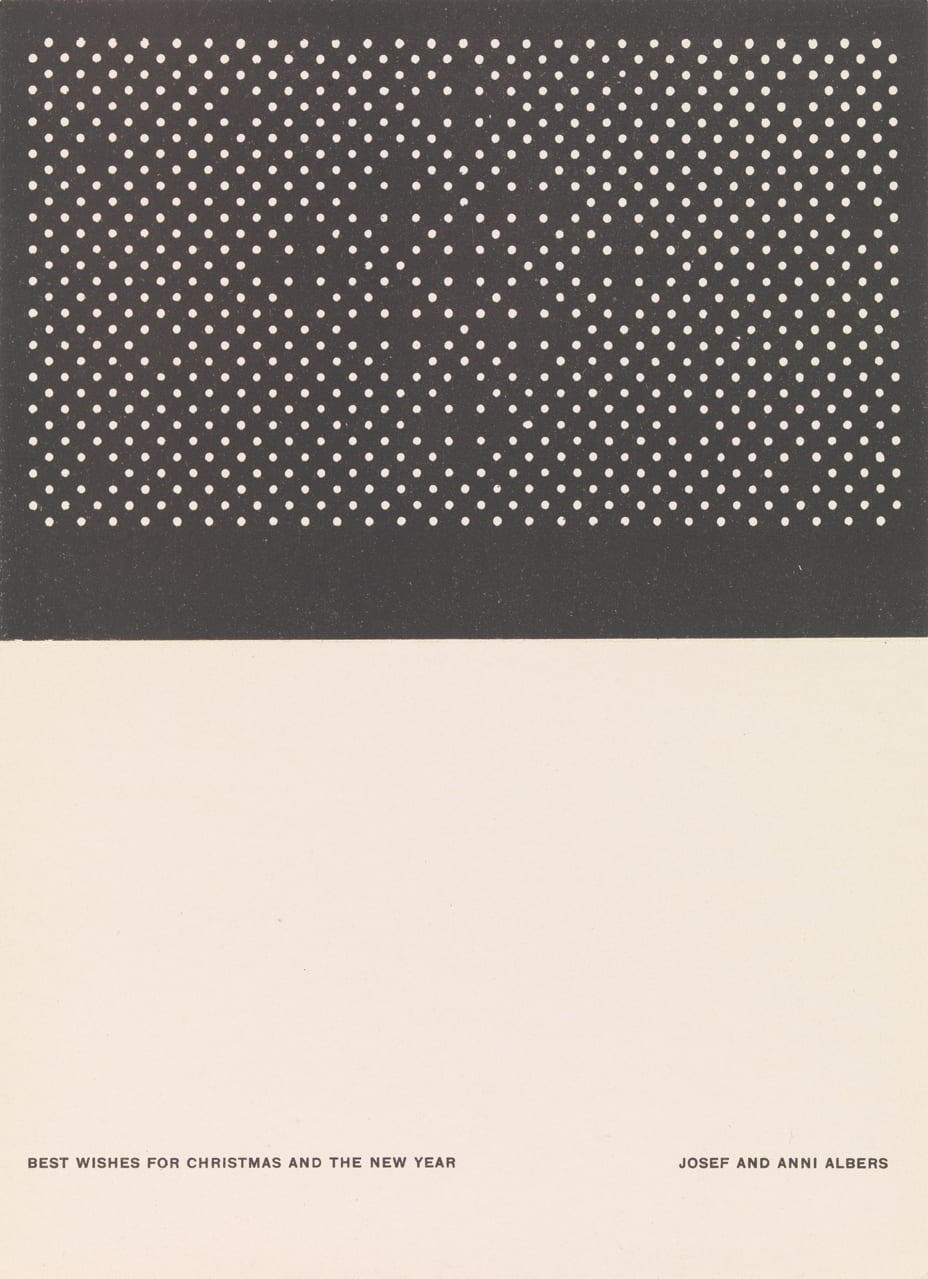

At first glance, the cards don’t exactly look like traditional Christmas notes (aside from the usual refrain, “Happy Christmas and Happy New Year, Josef and Anni Albers”). Rather, each one is its own exploration in graphic design, featuring details like textile-inspired dot patterns, abstracted letterforms, and hand-altered postcards.

The pair’s 1934 Christmas card was one of the first that Josef printed at Black Mountain College. Its simple, all-caps red font reflects a distinctly Bauhaus emphasis on simplicity and legibility over ornamentation, while the composition as a whole embraces the design ideal of balanced asymmetry. Weber once told Dezeen of Josef and Anni’s shared design philosophy, “They were both very interested in form following function. Everything was about process and understanding the materials and technology of putting them together.”

In later years, particularly between 1950 and 1960, the cards demonstrate a growing fascination with shape and line, using a minimalist black and white palette as a starting point. In 1951, a partially erased grid suggests the outline of a Christmas tree. The following year, a pattern created solely from white dots evokes a kind of festive textile, reminiscent of some of Anni’s groundbreaking work in the weaving space.

A christmas tradition

A closer inspection of the cards, Weber says, reveals some clues as to how the Albers spent their Christmases.

“There were a lot of things they didn’t do, but in their own simple way, they celebrated Christmas,” he says. “I say their own simple way, because they spent it at home together—not socializing—and listening to Bach’s Goldberg Variations. When you look at the holiday cards, you can really practically imagine the clarity of the Goldberg Variations: a lightness, a certain rhythm.”

Beyond the main art displayed on each card, the Albers also paid close attention to each missive’s actual construction. The letters were so well-made, Weber says, that many of the Albers’ friends framed them every year.

“The holiday cards relate very closely to the Albers’ very beautiful stationery. We’re talking about the days when a lot was done by letter. Anni and Josef had particularly handsome letterheads—you knew that every detail of the spacing was given great consideration. The cards are in the tradition of the letterheads. The holiday itself was important to both of them; they both had a sense of Christmas tradition,” Weber says.

Anni, for one, came from a wealthy background, once sharing with Weber her distinct memories of traveling by carriage to her uncles’ homes, where, alongside her brothers and sisters, she would eat delicacies including beluga caviar, rock lobster, and an ice cream cake. Josef, who grew up in a middle-class household, enjoyed these tales of excess. In 1975, Weber personally purchased the ingredients for Anni and Josef to enjoy a Christmas dinner reminiscent of those luxurious early years. That holiday season was ultimately the last that the two shared, as Josef died the following March.

“To this day, at Christmastime, I crave the pure tastes of the Alberses’ last Christmas together and must have one such atavistic meal,” Weber wrote in an essay on the topic for Air Mail last year. “And I listen to Glenn Gould playing that phenomenal music of Bach, aware that in Leipzig, Josef had made wonderful stained-glass windows very near to the church where Bach had long been organ master, and that the sublime intelligence of Bach suited the Alberses perfectly.”