One of the benefits of rewatching your favorite holiday films year after year is getting the opportunity to take a deeper look into the stories. We’re all familiar with overt themes about how Christmas is a time for giving, togetherness, and Red Ryder carbine-action, 200-shot range model air rifles—but the hidden messages in these movies can also provide some surprisingly cogent financial advice. In particular, the Grinch and other Christmas movie villains teach some of the most useful lessons about money. Here’s how the worst characters in your beloved Christmas movies can change how you look at money.

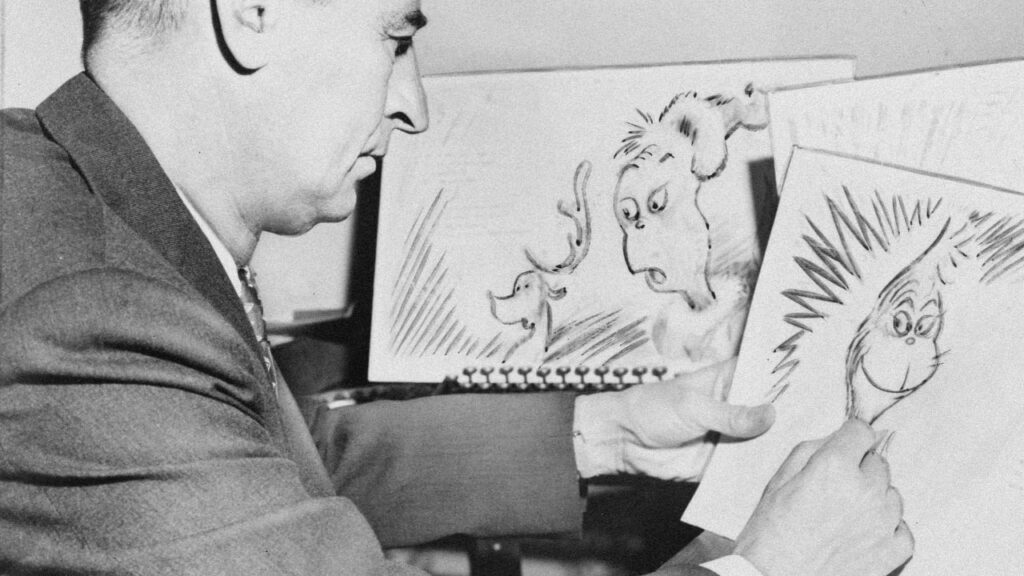

The Grinch reminds us to ask ourselves why

He’s a mean one, that Mr. Grinch. He steals Christmas just so the Whos down in Whoville can’t have it. While the noise the Whos make during their holiday celebrations could be an understandable complaint, there is no real reason for him to take out his frustration by snatching the roast beast (and stockings, ornaments, and other non-noisemaking holiday accouterments).

The Grinch should have questioned his own motives when little Cindy Lou Who finds him stealing her family’s Christmas tree and asks him, “Sandy Claus, why?” But our small-hearted anti-hero comes up with a lie instead of actually engaging with Cindy Lou’s question. However, the innocent query gets to the heart of what’s wrong with the Grinch’s plan.

The Grinch is looking to hoard Christmas because he doesn’t like that other people enjoy it. His “why” is both inherently selfish and short-sighted, since Christmas joy arrives in Whoville anyway, even without presents, decorations, or food. He didn’t actually want what he stole, and his theft didn’t do anything to stop the singing. Had he asked himself why, he might have realized what really wanted was to not be quite so alone.

While none of us wants to think we’re Grinch-like, it’s easy for us to treat money like he treats Christmas. Those of us who have enough may still want more without questioning why we want it. Getting more money can seem like an end in itself, but that may mean we don’t think through what it costs us to keep acquiring more, and we don’t figure out what it is we really want.

Mr. Potter teaches us that the power of money has limits

A key figure in the long line of Chirstmas baddies that includes Scrooge and the Grinch, the villain of the 1946 classic It’s a Wonderful Life is the heartless Mr. Potter, who owns the bank and most of the town of Bedford Falls. George Bailey’s Building & Loan is the only thing keeping Mr. Potter from completely dominating and destroying the small town.

In one of his more subtle attempts to dissolve the Building & Loan, Potter offers George a job for $20,000 per year (over $320,000 in 2024 dollars). While George is momentarily dazzled by the huge dollar amount, he quickly recognizes that taking the job offer will mean the downfall of the Building & Loan.

Later in the film, George’s Uncle Billy loses the Building & Loan’s $8,000 cash deposit (nearly $130,000 in 2024 dollars) by accidentally handing it over to Mr. Potter. When George approaches Mr. Potter to ask for a loan to replace the money, offering his small life insurance policy as collateral, Potter is delighted to point out that George is worth more money dead than alive.

Mr. Potter believes throughout the film that he should be able to get what he wants because he has money. He tries to entice George Bailey with a huge salary early on, and later assumes that he has George and his Building & Loan over a barrel because of the missing deposit. But in both cases, the power he wields with his money is no match for George’s idealism and morals and the respect the rest of the town has for him. The money Potter wields can’t deliver him the Building & Loan because there is a limit to the power of his wealth.

(That said, Mr. Potter does successfully get away with stealing the $8,000. Unfortunately, justice does tend to work differently for those with money.)

Hans Gruber shows us corporate greed is a type of terrorism

Alan Rickman’s portrayal of the faux-terrorist Hans Gruber in Die Hard is part of what makes this film as delightfully rewatchable as How the Grinch Stole Christmas or It’s a Wonderful Life. Gruber’s team claims to take the party guests at Nakatomi Plaza hostage for ideological reasons, but they are actually after the $640 million in bearer bonds (over $17 billion in 2024 dollars) hidden in the building’s vault.

Throughout the film, the Nakatomi Corporation executives hosting the office party are compared to Gruber. The sleazy Harry Ellis tries to befriend the terrorists by telling them, “Hey, business is business. You use a gun, I use a fountain pen, what’s the difference?” Similarly, Gruber remarks on Joseph Takagi’s John Phillips suit, saying that he has two himself. The audience is invited to see the parallels between the terrorists and the businessmen.

The characterization of protagonist John McClane as a regular Joe compared with Gruber and the businessmen helps reinforce the similarities between the terrorists and the corporate executives. McClane is a New York cop who is uncomfortable in a limousine and resentful of the gold Rolex watch his estranged wife Holly received as a gift. He spends the film fighting the terrorists while also trying to win Holly back from her new life and corporate career.

When Gruber grabs onto Holly’s Rolex in the finale, the connection between terrorism and corporate greed goes from metaphor to reality. The watch represents the Nakatomi Corporation, since it was a gift to Holly from her workplace, and the greedy Gruber grabs onto it in a last-ditch effort to kill Holly and McClane. Only by unclasping the watch–releasing his wife from the thrall of corporate greed–can McClane kill the terrorist.

Learning from villains

Curling up with a classic Christmas movie is a delightful way to spend a snowy evening. But while you watch, remember that even the characters you most love to hate can teach you something unexpected.

In addition to letting your heart grow three sizes, remind yourself to ask why you sometimes act Grinchly. While you feel the warm truth that no one is poor who has friends, take the time to be thankful that money’s power is limited. And as you enjoy the seasonal cries of Yippee-Ki-Yay, remember there’s a thin line between greed that destroys via business practices and greed that destroys via terror plots.