Great transmedia storytelling shows me that a single piece of media is just one limited window on a larger world. It invites me to imagine a universe that extends far beyond what I can see on screen or understand directly through the text. Telling multiple stories in the same universe, across different media formats, demonstrates that each character, place, or point in history presents just one out of many possible perspectives. To develop our own perspective, we take on board these different points of view and imagine what might exist out there that connects it all, a kind of “blind men and the elephant” exercise

In my chapter in Imagining Transmedia, “Cis Penance: Transmedia Database Narratives,” I discuss my own interactive documentary work about transgender people (specifically, a piece called Cis Penance: Trans Lives in Wait), in terms of concepts that come from Japanese media studies scholarship: database narratives and sekaikan (worldview). These can be considered alongside related concepts such as “storyworld” and “cinematic universe”.

Database narratives (or “database consumption”) is a concept introduced by Hiroki Azuma in the 2001 book Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals to describe a way of relating to media products that had become very prominent in Japanese otaku culture by the late 1990s. To take a well-known example, each Pokémon game, anime, movie, and other media extension contributes to a larger picture of the storyworld, establishing an overarching fictional reality through the narrative device of the Pokédex—though database consumption does not require this kind of in-world database. Database narratives or database consumption can also be observed in Star Trek, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the Hellaverse of Hazbin Hotel and Helluva Boss, and many more.

Rather than pointing to a singular, overarching “grand narrative” associated with modernism, in database consumption each person creates their own internal database of associations with a storyworld. Although “database” does not refer to a media object in itself—Azuma’s database is a metaphor for an imagined cognitive rendering of a storyworld inside a fan’s head—fan wikis are interesting texts to refer to when making sense of a database narrative, and represent an effort to negotiate a shared metatextual reality with other fans. Azuma’s argument is that otaku do not just consume the text of a particular piece of media, but more broadly consume the world that it portrays: its “sekaikan”.

I am generally grumpy about the introduction of loan words from Japanese into English, because their acquired meaning in English will inevitably come to differ significantly from their associations in Japanese. Part of this is due to the same inevitable semantic drift that plagues all language, but it may also be exacerbated by a strong tendency to exoticise “the Far East”. From “ikigai” to “katsu curry”, we just don’t seem to be able to resist making Japanese words into something they are not.

With that said, I find sekaikan legitimately useful, because it does point to something that is not quite captured by its English and German equivalents (worldview and Weltanschauung, respectively). Sekaikan is not just a set of beliefs about a world, but also how a world is portrayed in a piece of media. In English, we think of worldview as a philosophical position that “underlies” a work, a prior cause from which our narratives emerge. Sekaikan can mean this, but it can also refer to the outcome of a set of creative decisions. Rather than betraying the auteur’s underlying values, the creative process can itself produce a sekaikan, as part of its aesthetic effect. A worldview is something I have, but a sekaikan is something I try to create.

It might also be worth noting that when translating from Japanese to English, you often have to infer from context whether a noun is singular or plural, and whether to apply “the” or “a”. When we talk about worldview, we assume that the “world” in question is the consensual reality that we share with every other living being—there is only one “real world” with reference to which our worldviews are formed. Sekaikan is more freely used to describe how a fictional world is portrayed, independent of any beliefs the authors may have about the real world. Is the sekai of sekaikan “the world”, “a world”, or (many) “worlds”?

Another linguistic pleasure I get from “sekaikan” is that the character that translates to “view” is homophonous with another common suffix that translates to “feeling” or “sense of” (e.g. 疎外感 sogaikan, (feeling of) alienation; or 親近感shinkinkan, (sense of) affinity). Sekaikan does not mean “world feeling”, but it almost feels like it could (perhaps in another world?). Of course, here I’m doing the very thing that frustrates me about loan words—I’m making the word into something it is not, simply because it supports my own sensibilities and interests.

Just as we can construct database narratives about fictional worlds, I think we do the same about our own societies. I came to understand what it means to be a genderqueer person and a transgender man because I encountered the stories of other transgender people, through meeting people in LGBTQ+ community spaces, watching documentaries made by other trans people such as Fox Fisher’s My Genderation project, exploring trans people’s blogs and video-blogs, and playing indie games in the early years of the queer games movement. Each individual story contributes to a larger reality—a world in which gender identity exists independently of sex assigned at birth, gender dysphoria causes significant distress that one might only recognise after unlearning lifelong dissociative habits, and gender euphoria can be experienced by trans and cis people alike. Each testimony adds to my own internal database of things it is possible to feel, be, see and do.

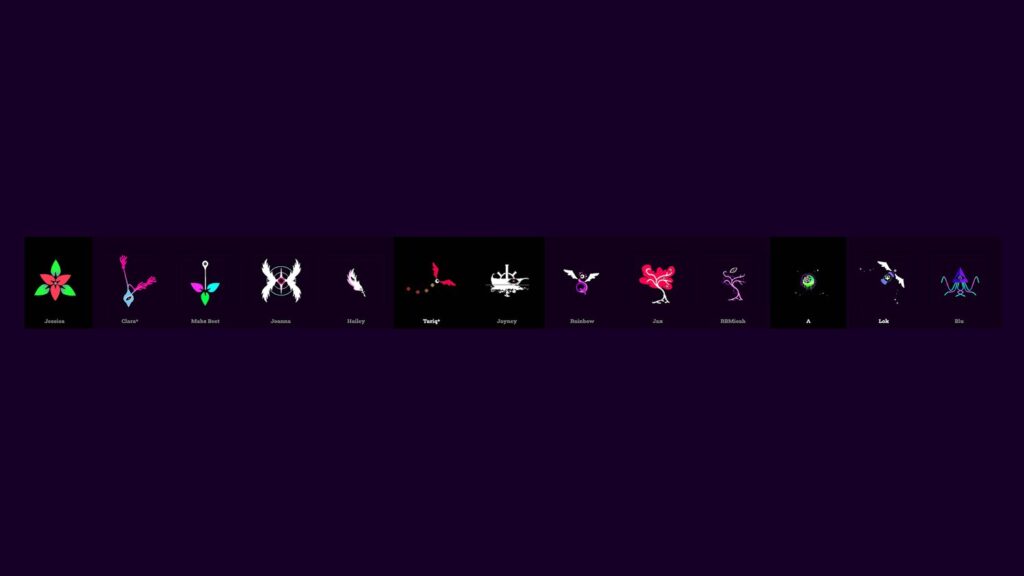

This construction of a sekaikan in which trans lives are possible was part of the purpose of my own work creating interactive documentaries based on oral-history interviews with transgender people. My first such work was created in 2018, when I was an artist in residence in Tokyo with a programme supported by the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs. I interviewed transgender people in the Kansai and Kanto areas, and turned each transcript into an interaction with an on-screen character. All the text attributed to that character came verbatim from one of the interviews, but to keep the interaction loop short I invented questions that the user could choose from, employing an interaction pattern seen in many role-playing games.